Photo essay by guest contributor Martin Plaut, a fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, the former BBC World Service Africa editor, and the author of ‘Understanding Eritrea.’ You can hear him speak with Eritrea Focus chairman Habte Hagos in a special webinar with Freedom United in early October. More details coming soon.

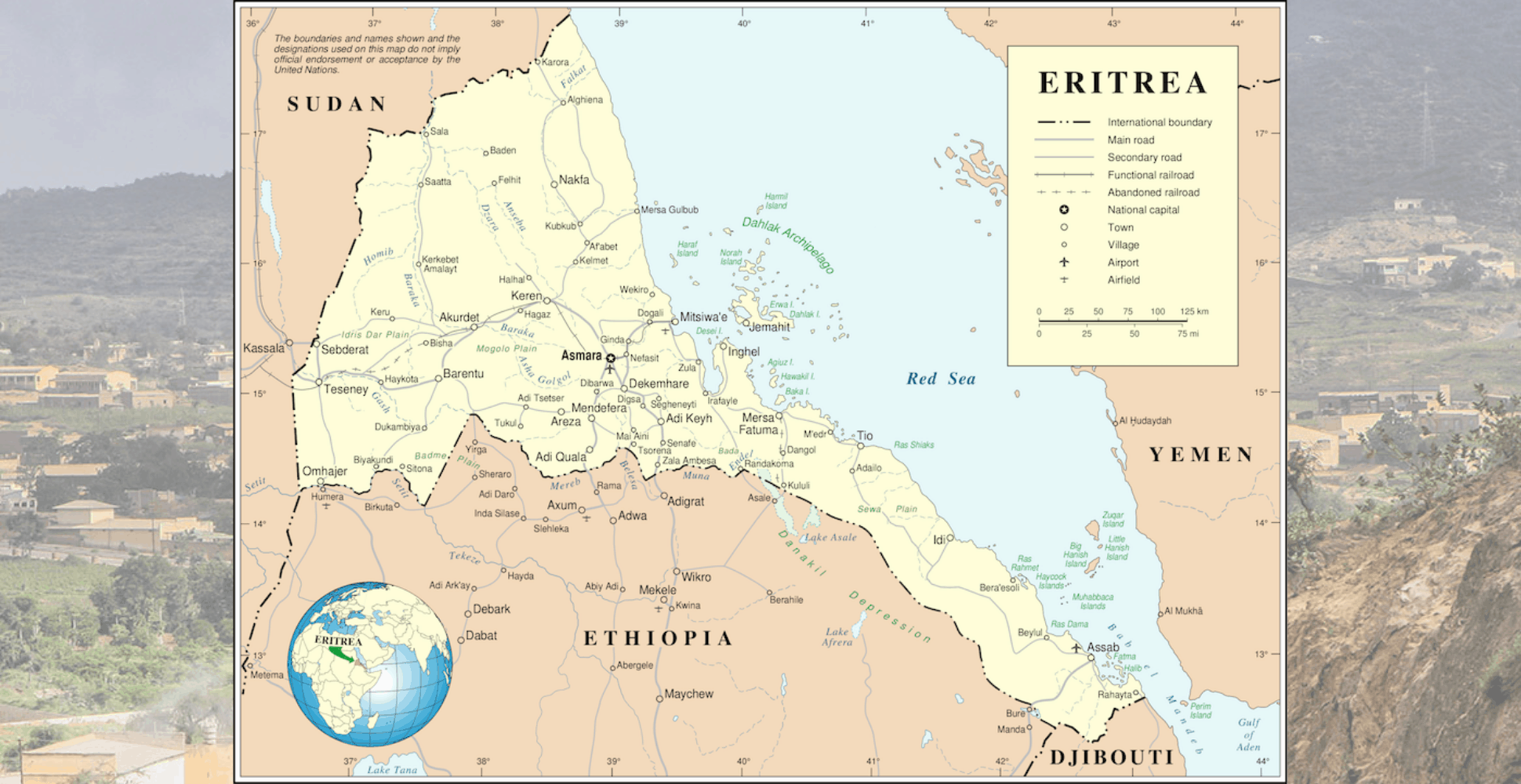

Eritrea, on the Red Sea, has been ruled by many nations. The Greeks, Egyptians, Turks and then the Italians held some or all of it. Eritrea has been Ethiopia’s gateway to the Red Sea. In 1935 the Italians, under the fascist rule of Benito Mussolini attacked Ethiopia, in an attempt to found a vast African empire. In 1941 the British freed Eritrea and restored the Ethiopian emperor to his throne.

1941-1961: War brews

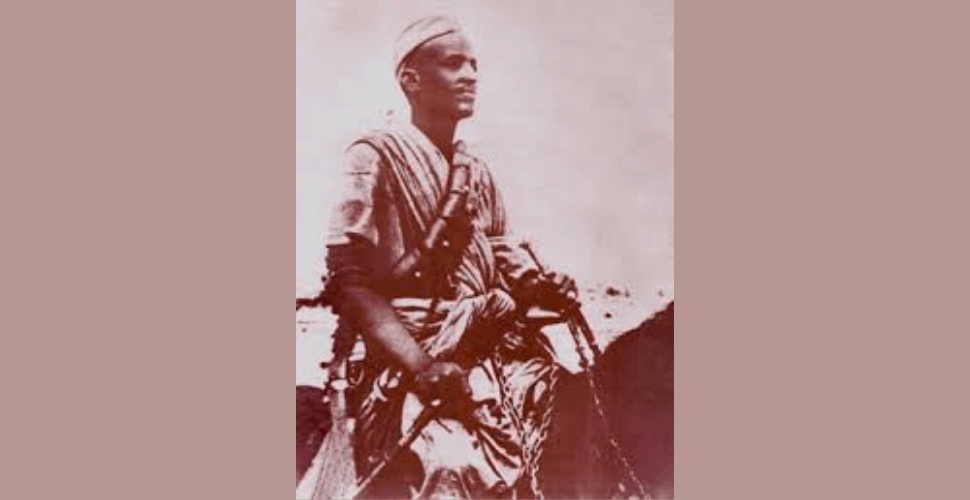

The British, having taken Eritrea, were left with a territory they didn’t want. They called on the UN to decide on Eritrea’s fate. After considerable controversy the UN awarded Eritrea to Ethiopia, but as part of a federation, to guarantee Eritreans a measure of autonomy and freedom. On 3 October 1952 the Emperor Haile Selassie, using golden scissors to cut a ribbon, federated Eritrea with Ethiopia. The federation lasted until 1960, when Haile Selassie annexed Eritrea, turning it into a province and ending any autonomy. This sparked off Eritrea’s fight for freedom. On 1st September 1961 a group of rebels led by Hamid Idris Awate attacked police posts in the west of Eritrea: its war of liberation had begun.

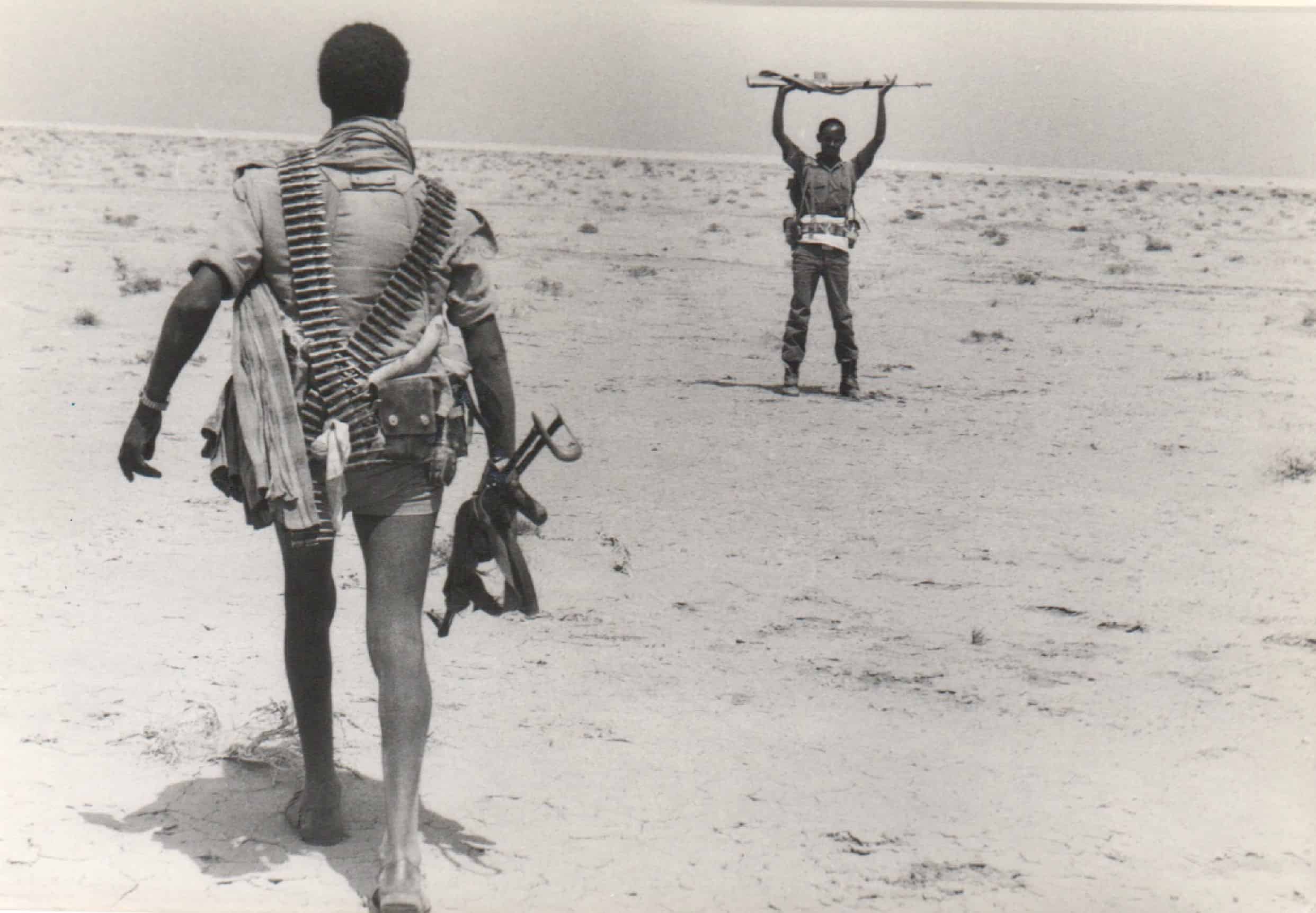

1961-1991: War of liberation leads to Eritrean independence

The war of liberation lasted 30 years. From 1961 its men and women fought relentlessly against Ethiopia whose population was ten times their size. Eritreans had some support from China and some Arab states, but fought mostly aided by donations from Eritreans living abroad. Ethiopia was armed first by the United States and then by the Soviet Union. Despite massive arms shipments, the Ethiopians were finally defeated in 1991.

1991-1998: Independence quickly gives way to dictatorship

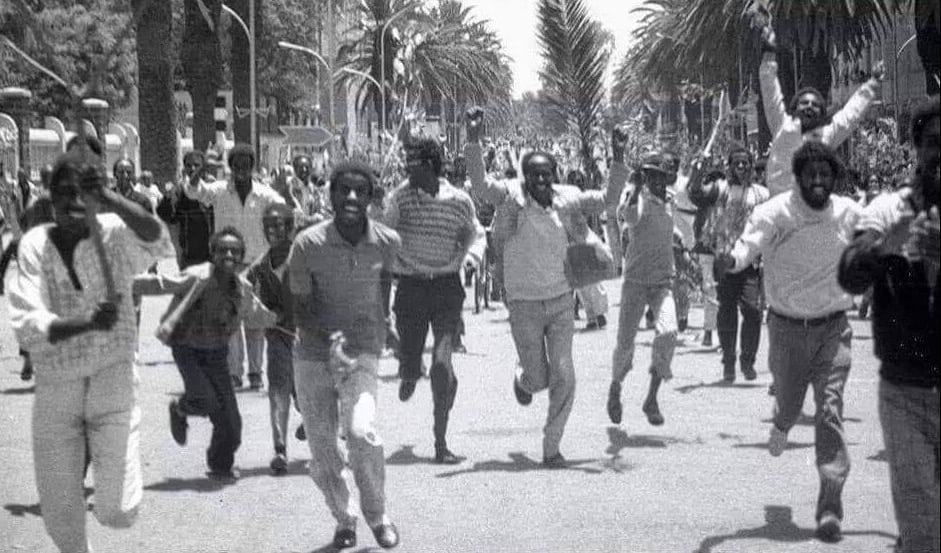

On May 24, 1991 Eritrean forces entered their capital, Asmara, to wild jubilation. The country was formally declared independent after a UN supervised referendum in 1993. Ethiopia recognized Eritrea as a sovereign state and at first relations were good. Eritreans began rebuilding their shattered nation. But two trends developed. President Isaias Afwerki, who had led much of the liberation war, gradually showed his true colors as a dictator. Elections were not held, no opposition parties tolerated and critics were rounded up and imprisoned without trail. Secondly, relations with Ethiopia slowly deteriorated.

1998-2020: War breaks out and ends in stalemate

A bitter border war erupted between Eritrea and Ethiopia in 1998. After more than two years Ethiopia had driven deep into Eritrea and the war was only ended with African, European and American mediation. Peace was signed in 2000 between President Isaias of Eritrea and Ethiopia’s Prime Minister, Meles Zenawi. This established an international commission to finalize their disputed border and award compensation for the conflict which had cost around 100,000 lives. But when a key decision went against it, Ethiopia refused to accept the outcome. The result was a cold “no-war, no-peace” ceasefire, with thousands of troops all along the border.

2020: Stalemate ends

On 18 July 2018 Ethiopian Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, arrived in the Eritrean capital, ending this stalemate. Eritreans were delighted and for a while relations between the two countries improved. The border was opened and trade resumed. But the thaw in relations did not last. The border was closed and tensions remain between Ethiopia and Eritrea – despite periodic visits by their leaders to each other’s capitals.

Forced labor today

For young Eritreans little has improved. They are required to end their education in the military training camp of Sawa. From then on they are trapped in “National Service” under military discipline. Although this was meant to least for just 18 months it can last for 20 years or more. The conscripts are paid little more than pocket money. Violence is rife, with sexual abuse against women conscripts. The UN Human Rights Commission has declared this a form of slavery. Yet all government projects, including roads being built with European Union money, rely on these “slaves” to do the work. Without rights, unable to appeal, many thousands of desperate Eritreans flee abroad, seeking a better life.

Read more about the campaign and add your name here.

-

Follow us on Facebook

5.6M

-

Follow us on Twitter

32K

-

Follow us on Instagram

8K

-

Subscribe to our Youtube

5.7K

Donate