“I spent 25 years in slavery. It was traumatizing, it was painful, physically and mentally. I felt sub-human, demeaned, socially dead.” – Curtis Ray Davis II, Executive Director of Decarcerate Louisiana, and formerly incarcerated

A staggeringly disproportionate number of Black Americans are part of the estimated 2 million people incarcerated in the United States right now. All of them are caught in a legal system of slavery.

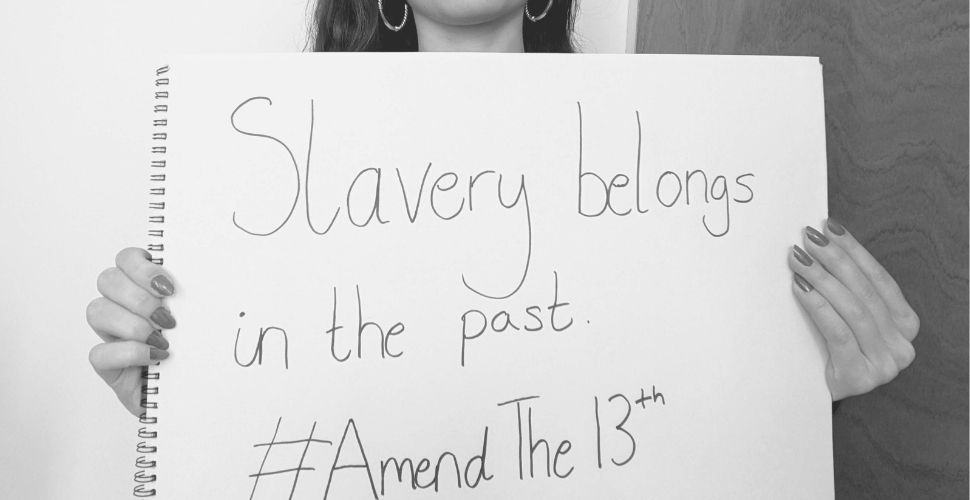

Despite its stated objective to abolish slavery in 1865, under the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution slavery and involuntary servitude remain legal as punishment for a crime through the “Exception Clause”. This means that for incarcerated people, being subjected to forced labor behind bars is an everyday risk.

It is shocking that in the 21st century, the U.S. is still grappling with the legacy of racist policies in the form of a legal system of slavery perpetuated through mass incarceration and the prison industrial complex.

The exploitation of U.S. prison labor runs deep into our supply chains. Mechanisms such as the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program, through which corporations are incentivized to “establish joint ventures with federal, state, local, and tribal corrections agencies”, are indicative of an inherently exploitative system of intertwined government and corporate interests that create the conditions for forced and coerced labor in detention to thrive. The “Exception Clause” leaves incarcerated people completely unprotected from forced labor at the hands of corporations.

A racial justice issue

According to the Sentencing Project: “Black men are six times as likely to be incarcerated as white men […] For Black men in their thirties, about 1 in every 12 is in prison or jail on any given day.” This is not only a human rights issue but a racial justice issue. As President Joe Biden announced at the start of Black History Month a few weeks ago, there is a need to “reckon with centuries of injustice, and confront those injustices that still fester today.” Outlawing slavery is a good place to start.

Though the ILO states that incarcerated people should not be forced to work under threat of penalty, it is evident how the prison industrial complex in the U.S. falls far short of these international standards. People incarcerated in the vast U.S. prison system report being threatened with solitary confinement, limited visitation rights, physical abuse, limited access to food and longer sentences if they refuse to work.

Lawmakers taking action

Fortunately, we are seeing progress. Last year, Senator Jeff Merkley and Representative Nikema Williams introduced the Abolition Amendment, a joint resolution to strike language permitting slavery as punishment for a crime from the U.S. Constitution. Lawmakers across the U.S. are also making progress to eliminate language in their state constitutions that still allow slavery as punishment for a crime. Since 2018, Colorado, Utah and Nebraska have successfully eliminated the “Exception Clause” from their constitutions. And in 2021, Senator Zellnor Myrie introduced a bill in New York State to prohibit involuntary employment of prisoners.

More than 13,000 of you have added your voice calling on Congress to pass the Abolition Amendment – but there is still a long way to go. That’s why we need to keep the spotlight on this issue to see Congress take action.

Reflecting on history, it becomes clear that the proliferation of forced prison labor is an intentional component of a fundamentally inhumane prison system designed to provide labor for pennies to line the pockets of corporations.

How did we get here?

The passage of Jim Crow laws following the abolition of chattel slavery, whereby a person could legally own another as property, intended to maintain the segregation and subjugation of Black Americans through limiting their newfound freedoms. Black Codes and vagrancy laws immediately followed the formal and incomplete abolition of slavery in a concerted strategy to effectively re-enslave emancipated Black Americans.

Under vagrancy laws, those perceived to be unemployed or homeless could be arrested, imprisoned and leased out to undertake brutal work for no pay in dehumanizing and violent conditions that were no different, and in some cases worse, than chattel slavery.

The practice of “convict-leasing” saw tens of thousands of predominantly Black and brown Americans in the Southern states leased out by the U.S. government as cheap labor to private companies and individuals to work on plantations, railroads, coal mines and other key industries. Thousands died in order to protect companies’ profits.

Though “convict-leasing” was phased out throughout the 20th century, other forms of forced penal labor quickly replaced it in the form of chain gangs, particularly in the Southern states. Alarmingly, it’s not over. The systematic and intentional system of forced prison labor persists today, disproportionately affecting Black and brown Americans.

We know you agree slavery belongs in the past. Let’s make sure the U.S. hears our collective call – add your voice to the campaign today.

I don’t agree with this. What are we supposed to do with this people? Some worth has to be derived. Banning grossly inhumane conditions, yes. Stopping all labor, no.

I disagree with several of your spirited, persuasive statements. Could you not praise the emancipation proclamation, or celebrate our victories? The framing of your arguments, though forceful in speech, are off-putting. I’m already dedicated to ending forced labor. Please consider this when addressing your audience. I feel attacked rather than informed.

I would like to better understand this by knowing specifics of what is presently happening within the prison system.

Prison reform is a process – and it is my hope that one day we will see a prison system fully staffed to equip the incarcerated for a successful life beyond the prison walls. Counseling, job skill development, education, medical assistance are all components for upgrades and reform.